Zero Suicide is a transformational framework for health and behavioral healthcare systems.

The foundational belief of Zero Suicide is that suicide deaths for individuals under the care of health and behavioral health systems are preventable. For systems dedicated to improving patient safety, Zero Suicide presents an aspirational challenge and practical framework for system-wide transformation toward safer suicide care. Visit the Zero Suicide website homepage here.

The Zero Suicide toolkit.

The Zero Suicide toolkit uses research, tools, and videos to walk implementers through putting the Zero Suicide Framework into practice.

The Zero Suicide Toolkit Adaptation for Indian Country can be used as a supplement and provides best and promising practices for operationalizing the Zero Suicide Framework for health and behavioral health systems in Indian Country.

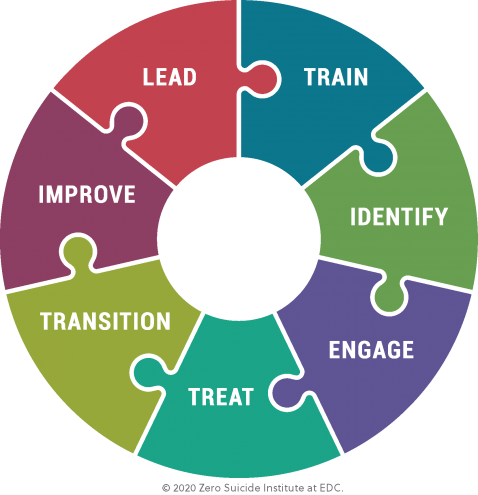

The seven elements of Zero Suicide.

The Zero Suicide Framework includes seven elements that work together to transform suicide care in health systems.

Lead system-wide culture change committed to reducing suicides.

Train a competent, confident, and caring workforce.

Identify individuals with suicide risk via comprehensive screening and assessment.

Engage all individuals at risk of suicide using a suicide care management plan.

Treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors using evidence-based treatments.

Transition individuals through care with warm hand-offs and supportive contacts.

Improve policies and procedures through continuous quality improvement.