Infection Prevention Orientation Manual

Section 16: Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement

Ellen Williams, RN, BA; Pat Fritz, RN, BC, WCC, NHA; Ann Lovejoy, MBA, M.Ed.

October 2014

Download a printable PDF Version of this section.

Objectives

At the completion of this section the Infection Preventionist (IP) will:

- Utilize or update the facility’s written plan for infection prevention (aka Infection Prevention Plan) to include an assessment of risk, services provided, the population served, strategies to decrease risk, and a surveillance plan

- Describe the rationale for collecting infection prevention data and other appropriate data for his/her facility

- Utilize infection prevention data to identify processes that are at risk of causing an infection or safety issue for patients, visitors, or staff

- Use the facility’s performance improvement model (e.g. Plan, Do, Study, Act [PDSA]) to improve infection prevention processes prioritized in the Infection Prevention plan.

- Establish or strengthen the facility’s working Infection Prevention committee

Number of hours

- Key Concepts and Methods combined – 8-10 hours

Overview

Infection Prevention is a key component of system-wide quality assurance and performance improvement activities.

Hospitals, long-term care facilities, ambulatory surgery centers, and dialysis facilities are required to assure quality and safety for patients, staff, and visitors. The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), state regulators, and accreditation bodies recommend that a Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI) program be in place and provide evidence demonstrating continuous improvement. A QAPI program consists of systematic and continuous actions that lead to measurable improvement in healthcare services and the health status of targeted patient/resident groups. A QAPI program has five elements:

Element 1: Design and Scope are patient-or-resident focused, ongoing and comprehensive.

Element 2: Governance and Leadership drive a culture of quality.

Element 3: Feedback, data systems and monitoring are in place to create and implement action plans for quality and safety improvement.

Element 4: Performance Improvement Projects are conducted to improve care appropriate to the type of facility and scope of services.

Element 5: Systemic Analysis and Systemic Action includes ongoing methods to maintain improvements via policies, standard processes, procedures and performance management.

Key Concepts

Infection Prevention Program

Nationally recognized infection control practices or guidelines, applicable regulations of other federal or state agencies, and standards of accreditation are requirements to set the direction for infection prevention programs. The facility’s program for surveillance, prevention, and investigation of infections and communicable diseases should be conducted in accordance with these existing requirements. Additionally, the facility’s infection prevention program must be integrated into its facility-wide Quality Improvement (QI) or QAPI program.1

Goals of the infection prevention program are to:

- Decrease the risk of infection to patients/residents, visitors, and healthcare personnel

- Monitor for occurrence of infection and implement appropriate prevention measures

- Identify and correct problems related to infection prevention practices

- Limit unprotected exposure to pathogens throughout the facility

- Minimize the infection risk associated with procedures, medical devices, and medical equipment

- Maintain compliance with state and federal regulations related to infection prevention.2

Accrediting bodies describe methods for how these goals are met. For example, The Joint Commission, www.jointcommission.org, states a comprehensive infection prevention program has a detailed strategic plan that:

- prioritizes the identified risks for acquiring and transmitting infections

- sets goals that include limiting: (a) unprotected exposure to pathogens; (b) the transmission of infections associated with procedures; and (c) transmission of infections associated with the use of medical equipment, devices, and supplies

- describes activities, including surveillance, to minimize, reduce or eliminate the risk of infection

- describes the process to evaluate the infection prevention and control plan.

Infection Prevention Plan

The Infection Prevention Plan (IPP) is used to assess risk factors, and assure the detection, prevention, and control of infections among patients/residents, visitors and personnel. The scope of services depends on the patient/resident population, function, and specialized needs of the healthcare facility. Completion of a risk assessment, data gathering, and analysis should always drive the plan. The plan should be a working document, reviewed and revised at least annually. The Infection Prevention Plan sets a clear direction for the facility with goals and objectives and establishes processes to identify and reduce risks of infection for patients/residents, visitors, and healthcare workers.

Quality Assurance and Preformance Improvement (QAPI) Plan

While the IPP is the strategic plan for preventing infection in the facility and community, the QAPI plan is the treatment plan for the facility to make infection prevention and quality improvement happen. The QAPI plan is based on information in the IPP and provides the details of what and how infections will be prevented and processes identified as needing improvement. Data drives the QAPI process. 3 The QAPI plan must outline time-framed and realistic goals and include related performance measures that are responsive to the prioritized risks in the infection prevention plan.

Quality improvement projects always begin with a QAPI plan. The team-based actions to complete the QAPI plan include the following steps to prepare, write, and evaluate the implementation of the plan:

Step 1: Determine what area(s) of improvement the facility needs to focus on and identify people/disciplines using or affected by the process. It is impossible to fix/improve every problem identified at the same time. To focus infection prevention quality improvement efforts:

- Review the IPP to determine high risk and/or high volume incidents to facility and community

- Identify the measures required by regulatory bodies

- Identify the measures that are in alignment with the facility’s mission

- Identify the measures required for initiatives the facility participates in such as the Quality Information Organization Healthcare-Associated Infection (HAI) prevention project, CMS Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting, &/or Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project.

Step 2: Manage data for performance improvement. Analyze how the facility is collecting, tracking, analyzing, interpreting, and acting on the data. Determine what data to collect for each focus area, how to obtain the data, the person responsible for obtaining the data, the frequency data is to be collected, and how/when the data is reported. Include the information technology department to facilitate electronic data collection when possible. Identify baselines and set targets for improvement.

Step 3: Identify potential barriers related to the problem or process to improve. Appendix A illustrates a Barrier Identification and Mitigation (BIM) Tool4 to help the QAPI team systematically identify and prioritize barriers. Barriers can relate to characteristics of the clinicians, the work environment, the culture within the organization, available resources, and many other factors. After the team understands the underlying reasons for the barrier, develop a plan to mitigate the barrier.

Step 4: Write and finalize the specific QAPI plan based on the selected priorities, barrier mitigation, and corrective actions steps the team has developed.

- Implement the action steps in the plan after approval by committees/administration designated by the facility. The plan can be modified as necessary by the IP and other committees determined by the facility.

- Obtain data to assess the success of the QAPI plan at designated point in times (e.g. quarterly, annually). Based on the analysis, determine the next steps. Post-plan evaluation can include but is not limited to5:

- Continuing the process as is with the same indicators/data monitoring

- Continuing the process with modifications (i.e., implement additional interventions to remove identified barriers)

- Adding new monitors/quality indicators

- Stop monitoring.

Step 5: As progress is monitored, report results of the QAPI Plan to key stakeholders at specified intervals. Include lessons learned along with other outcomes in the report. Take steps to celebrate successes.

Data Collection and Use

Data-enabled decision-making and improvement activities contribute to the quality of services provided to patients/residents. In addition to being a regulatory requirement, data collection assists the IP in:

- improving patient/resident satisfaction and confidence

- developing relationships with front-line staff

- identifying infection control and prevention risks

- developing a business case for improvement interventions

- making decisions about healthcare resource utilization

- determining if interventions are successful.

Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) Model for Improvement

When a problem is identified, a standard approach to address the problem is helpful. The PDSA model for improvement is a process commonly used to analyze a problem, develop solutions, implement improvement and evaluate the results.

Methods

Initiate Infection Prevention Program through Planning

The IPP is a roadmap for how the Infection Prevention Program will work during the year. The plan must be flexible to facilitate alteration in response to unexpected disease processes or environmental issues and yet contain specific, realistic, and measureable goals.

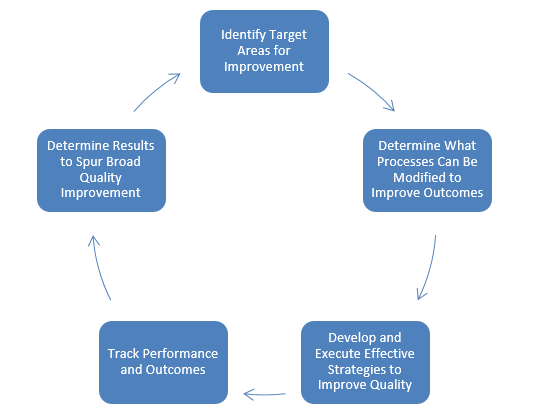

The IPP is used to determine quality improvement activities, increase adherence to infection prevention practices, improve patient/resident outcomes, and prevent HAIs. As seen in Figure 1, quality improvement efforts typically involve five steps.6 Steps include:

- Identify target areas for improvement through a risk assessment and analysis

- Determine what processes can be modified to improve outcomes

- Develop and execute effective strategies to improve quality through an infection prevention or QAPI plan

- Track performance and outcomes

- Disseminate results to spur broad quality improvement

Figure 1. Steps in the Quality Improvement Process.6

The best way to involve people and their talents appropriately is to develop the plan using a team approach by engaging people in the Infection Prevention Committee. Meaningful, ongoing team activities may include periodic reviews of data, development of tools & processes to facilitate implementation of best practices, and feedback to staff and administration. Multidisciplinary teams increase problem identification and solution development. Utilization of patient/resident and front-line staff expertise and knowledge of the problem can improve interventions and implementation processes. A full evaluation of the IPP should be done annually.

The Infection Prevention Committee minimally consists of a physician, front-line nursing staff, quality improvement/risk management staff, and representatives from microbiology, central sterilization, environmental services, pharmacy, and administration. Additional staff members may be asked to provide input or join the committee as issues arise.7, 8

Exercise #1

Find or create a list of the members of your infection prevention committee or the committee that reviews the infection prevention data and antibiotic use. Is there appropriate representation on the committee? Administrative? Scientific and credentials? Various key areas such as pharmacy, lab, ICU?

- Contact each member to introduce yourself.

- Identify with them any needed additional members or experts who can be called upon.

- Introduce yourself to front-line staff and managers throughout your facility. Enlist their support to work together to prevent infections and increase patient/resident safety.

Note: If you do not have an infection prevention committee or a committee who reviews the infection prevention data and antibiotic use, talk with your supervisor regarding staff that would be appropriate to work with you.

Infection Prevention Program Roles and Responsibilities

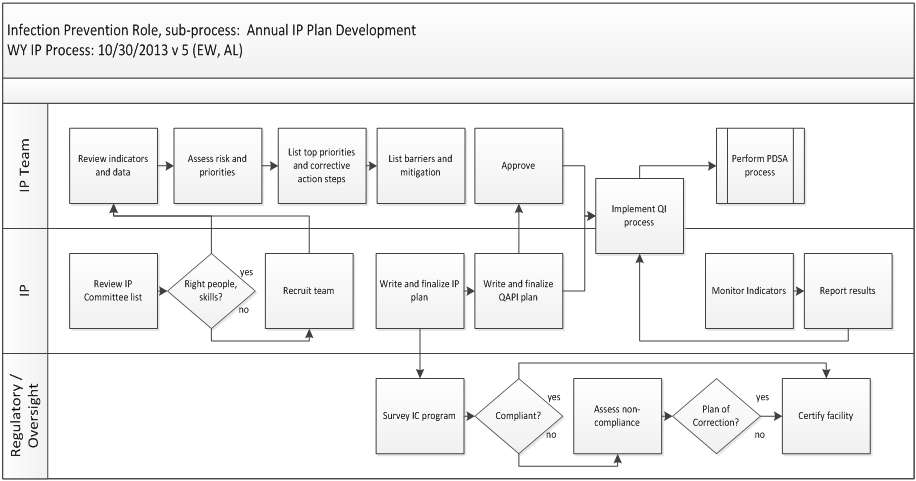

The infection prevention program involves many stakeholders, both on and off of the infection prevention committee. Roles and responsibilities for how the regulatory bodies, IP and IP Team work together to create or update a plan are shown in Figure 2. To read the work flow, begin in the upper left corner of the top IP Team role lane. Follow the arrows. Joint actions appear in Figure 2 as action-step boxes that straddles the line between two or more roles.

Figure 2. Roles and Responsibilities for Infection Prevention Plan Development. Abbreviations include: IC (Infection Control), IP (Infection Prevention Professional), PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act), Plan of Correction (a Corrective Action Plan), QAPI (Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement), QI Process (Quality Improvement).

Analyzing Risks and Setting Priorities for Action

Individuals delivering clinical and care-related services are frequently not on the infection prevention committee. The team and relationships the IP builds in the facility assure individuals will take the risk of infection seriously and facilitate their engagement. Their collaboration and behavior are very important to reduce or eliminate risks of infection.

Identifying the risks is not enough to prevent infections. Risks must be analyzed for severity and the actual frequency of occurrence in a facility. This analysis helps the committee prioritize the risks identified during plan development or update. The IP and the committee have a finite amount of time and resources and are more likely to be successful in reducing risks if they focus on a few key items.

There are many tools available to help identify and prioritize infection risks. It’s best for the IP to select a tool to help define a prioritization method. Appendix B provides examples of these tools. A team-based review of the priorities by the infection prevention committee is helpful. Documenting the prioritized risks and rationale for selection helps people outside the team accept and spread improvements throughout the facility. The more people engaged with the goals, the better.

Exercise #2

Locate the risk assessment and infection prevention plan that was created for your facility. Review infection data for the past 1-2 years. Are there patterns? Recurring incidents? Note location, type, severity and frequency. Compare your analysis to the Infection Prevention Plan section regarding risks. Does the plan describe actions that are consistent with experience?

Facilitate the Infection Prevention team to clarify and discuss the risks.

Prioritize what key actions will be taken during the plan year.

Update the risk assessment potion of the plan based on the team’s knowledge and needs of the facility and community.

Note: If you cannot locate your facility’s assessment and plan, review the sample risk assessment and plan in Appendix B. Use one of the 3 templates in Appendices B, C and D to create a draft risk assessment and plan for your facility.

Designing and Implementing Solutions

Once a risk is identified and prioritized for action, a quality improvement solution is designed using a quality improvement model. Healthcare facilities can employ various approaches and models to improve quality including: Gap Analysis9; Root Cause Analysis 10, 11; Failure Mode Effect Analysis12; Strength, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats Analysis13; Multi-voting14; Goal-Directed Checklists15; Process Control, Charts, Graphs, and Clinical Practice Guidelines16; Six Sigma and Lean Approach17; and the PDSA Performance Improvement Model.18

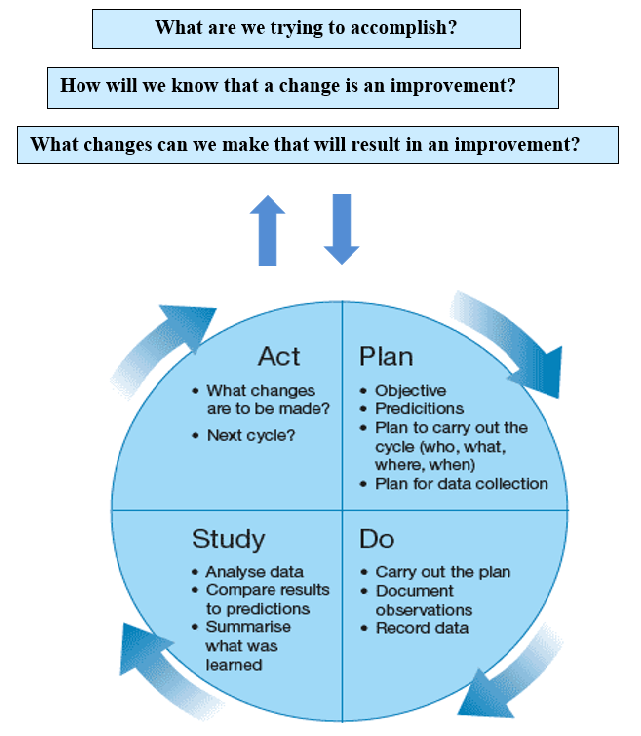

The PDSA Model for Improvement

The PDSA model for improvement18 is a four-step method used to implement a guideline or work flow change and process improvement. A team is established based on the risk or problem that needs to be improved. The team should include an administrative person who is able to allocate funds if needed; a front-line staff member who is involved in using the process, and a patient/resident representative when possible. The important elements of the PDSA improvement model are shown in detail in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Plan, Do, Study, Act Improvement model. 18

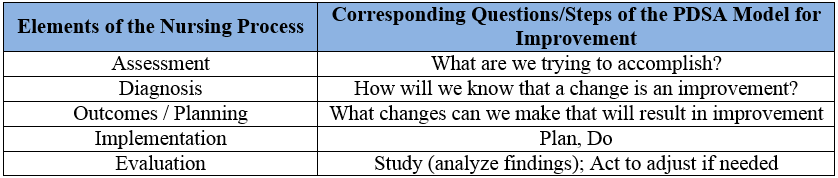

The PDSA Model tests implemented changes. Following the prescribed four steps (1) plan, (2) do, (3) study, and (4) act guides the thinking process. Each step helps assure good results, breaking down the task into reasonable steps, evaluating the outcome, improving on it, and testing again. PDSA is very similar to the Nursing Process (Appendix E) which includes the five elements of (1) assessment, (2) diagnosis, (3) outcomes/planning, (4) implementation and (5) evaluation. Each element of the Nursing Process corresponds with one or more of the initial questions and steps of the PDSA improvement model in Table 1.

Table 1. Elements of the Nursing Process corresponding to the PDSA model for improvement.

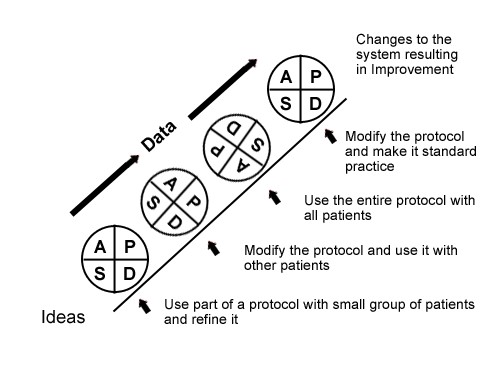

If the first PDSA attempt doesn’t completely solve the problem, additional improvement “cycles” may be done. After one cycle of all four steps, a new PDSA cycle begins from that point. These repeated uses of PDSA are also called “tests of change.” A schematic of this process of repeating PDSA cycles is shown in Figure 4.19 Repeated use of the PDSA cycle fosters improvement by successive refinements that are documented and enhanced. The IP must keep the following details in mind when using the PDSA model in cycles:

- Single Step – Each PDSA cycle often contains only a segment or single step of the entire process to improve quality.

- Short Duration – Each PDSA cycle should be as brief as possible in order to determine whether or not the intervention is working. Some cycles can be as short as 1 hour.

- Small Sample Size – A PDSA cycle will likely involve only a portion of the staff. Once initial feedback is obtained and the process refined, the implementation can be broadened to include all staff.

Figure 4. Sequential use of the PDSA model for improvement.19 Reprinted with permission from Associates in Process Improvement.

Exercise #3

Find the sample PDSA worksheets in Appendix F and H as well as a template for your use in Appendix G. Review the examples and template. Identify a problem to work through and complete the template. (Please download the printable PDF Version of this section, linked at the top of the page to see the Appendices).

PLAN

Background: the problem statement and the result desired.

Describe the solution to be tested: keep this specific.

List of tasks: pre-work before testing, what needs to be done, people to be informed and involved. Assign accountabilities, dates, locations.

Predict what will happen: identify a baseline measurement to use to evaluate the PDSA at the end.

DO

What was observed: write down the answers to questions such as

- What were reactions of patients/residents, visitors, staff?

- Did the intervention fit in with your system or process flow?

- How the intervention affected other parts of the process?

- Did everything go as planned?

- Did the team have to modify the plan?

STUDY|

Use the measurement you determined in a previous step, and study the results. List what was learned.

ACT

Summarize the conclusions about the method and results of the PDSA

Quality Improvement Measures and Reporting

Periodic review of performance is critical for assessing the effectiveness of quality improvement interventions. Process measures are concerned with activities within a care episode and relate to action steps such as patient safety and clinical procedures that are done consistently. Outcome measures are closely associated with patient/resident outcomes or results. Either kind of measure can be used to evaluate performance. Measures provide a common language with which to evaluate the success of interventions. Process measures include the goal of a 100% rate of adherence to the recommended practice and do not require adjustment for patients’ underlying risk of infection or severity of disease. Loosely, the words “measure” and “indicator” refer to quantitative ratios or comparisons that reflect the status of a process or result of a process.

In the 1980s, efforts began to promote public reporting of data by the Health Care Financing Administration (the predecessor of CMS). While public reporting of healthcare data has advanced considerably in depth and scope, it is still an evolving process. CMS posts performance information about cost and quality levels of providers such as hospitals, physicians, home health facilities, nursing homes, dialysis centers, and ambulatory surgery centers. Public reporting helps consumers make informed decisions when choosing a provider and to provide data for value-based purchasing of healthcare services by CMS and other payers. CMS provides healthcare data to the public via their website www.medicare.gov. Additionally, several private organizations report quality data in the public interest. Examples include: Leapfrog, Consumer Reports, UCompareHealthCare, Commonwealth’s Why Not the Best, and Healthgrades.

The additional transparency via the availability of information for consumers, has changed the behavior of staff within the healthcare industry. Interviews with hospital staff regarding the public reporting of quality measures in one study revealed common themes.20 Themes include:

- increased involvement of leadership in performance improvement

- created a sense of accountability to both internal and external customers

- contributed to heightened awareness of performance measures data throughout the hospital

- influenced or re-focused organizational priorities

- raised concerns about data quality and

- raised questions about consumer understanding of performance reports.

The healthcare industry is moving toward greater openness and accountability. A key result of this shift is clinical staff and leaders re-prioritizing healthcare quality improvement as a more important goal.

Infection Prevention Measures and Reporting

HAI data for hospitals is provided to CMS by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) via their electronic HAI tracking system called National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN).21 See Appendices I and J for a list of indicators currently reported publicly. While reporting is voluntary, Medicare payments are decreased if hospitals participating in the Prospective Payment System (PPS) do not collect and submit the required data. The data from several indicators are also used by CMS to calculate payments in the Value-Based Payments system. For the most current information on CMS public reporting and value-based programs see www.cms.gov and www.qualitynet.org. The CMS based their reporting requirements on a 1995 Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA; www.shea-online.org) position paper describing the criteria for selection of quality indicators.22 The SHEA criteria include: identifying quality indicator events that are clearly defined with numerators and denominators, using indicator variables that are easy to identify and collect, selecting data collection methods that are sensitive enough to capture the data and that can be standardized across all institutions, selecting indicator events that occur frequently enough to provide an adequate sample size, and comparing populations with similar intrinsic risks or providing appropriate risk adjustments.

Surveillance of HAIs initially focused on device- and procedure-associated infections because these infections occur among hospitalized patients and are associated with potentially modifiable risk factors. The most widely used definitions for healthcare related infections are the CDC definitions located on the NHSN website, www.cdc.gov/nhsn. The McGreer Criteria are used for long term care facilities and may be found at www.premierinc.com/quality-safety/tools-services/safety/topics/guidelines/downloads/25_itcdefs-91.pdf. These definitions were updated in 2013 and the newer version can be found at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3538836/.

Even when standardized NHSN and McGreer definitions are used, the interpretation of HAI definitions can vary between users and different approaches to surveillance applied. These variations in interpretation of available data sources and methods can adversely impact the completeness and comparability of HAI data.

There is growing evidence that HAI surveillance methods that use readily accessible automated data for screening are a more resource-efficient approach; however, these information technology applications cannot replace frontline surveillance by trained personnel. In addition, risk adjustment to account for underlying differences between healthcare facilities’ patient populations is essential for meaningful comparisons.23

For the IP, NHSN is the HAI surveillance gold standard because it provides:

- surveillance definitions and criteria for specific types of infections which facilitates data accuracy and consistency

- detailed training on the use of the system and help desk assistance

- analysis functions

- national data reports, and

- data security, integrity, and confidentiality.

The benefits to using NHSN are many, and most facilities utilize the system for the following:

- access NHSN enrollment requirements for CMS Quality Reporting programs

- obtain baseline HAI rates

- compare rates to CDC’s national data

- participate in state or national HAI prevention initiatives

- evaluate immediate and long-term results of infection elimination efforts

- refocus efforts as needed where actions are not working, or advance to different areas.19

The NHSN system requires facility and individual registration. To enroll a facility, an IP should visit the CDC NHSN website www.cdc.gov/nhsn/enrollment/index.html, click on the link for the facility type, and follow the instructions. When the facility enrollment process is complete, the NHSN facility administrator (person listed on the NHSN enrollment application) will receive an email with instructions for obtaining a digital certificate or an invitation to register for Secure Access Management Services (SAMS). CDC is in the process of initiating the implementation of the SAMS system. More information can be located at www.cdc.gov/nhsn/sams/about-sams.html. CDC provides training for each facility type, NHSN administrator and group roles, each NHSN module, and how to use the analysis feature.

Exercise #4

Check to see if your facility is already enrolled in NHSN. Determine who the NHSN administrator within your facility is and make sure the person is set up as a “user.” If the NHSN administrator has left the facility and is no longer available, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) will need to write a letter to NHSN identifying who the new administrator should be, including their email address. The letter can be sent to the NHSN help desk at NHSN@cdc.gov. It is very important to complete the NHSN training appropriate for the facility prior to entering any data into the system.

Tips for Success

Establish a culture of quality by demonstrating to the infection prevention team what infection prevention quality looks like for the organization. Communicate that vision to staff in the facility and to the community.

The structure and process for quality improvement should be visible and easily understood by everyone. Buy-in and support at all levels is essential to successfully implement the infection prevention and quality improvement plan. While quality improvement requires an investment of time, staff and fiscal resources, the benefits are improved patient/resident outcomes, increased efficiency, improved healthcare worker safety, improved customer satisfaction and potentially decreased costs.

Resources

Helpful/Related Readings

- Grota P, Allen V, Boston KM, et al, eds. APIC Text of Infection Control & Epidemiolo 4th Edition. Washington, D.C.: Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc.; 2014.

- Chapter 5, Infection Prevnetion and Beehavioral Interventions, by P Posa

- Chapter 16, Quality Concepts, by E Monsees

- Chapter 17, Performance Measures, by B M Soule and DM Nadzam

- Bennett J and Brachman P, eds. Bennett & Brachman’s Hospital Infection 6th Edition. 2014. Philadelphia, PA: William R Jarvis. Chapter 48, Patient Safety, by ML Ling

- Bennett G. Infection Prevention Manual for Ambulatory Care. Rome, GA: ICP Associates Inc.; 2009. Section 10

- Bennett G and Kassai M. Infection Prevention Manual for Ambulatory Surgery Centers. Rome, GA: ICP Associates, Inc.; 2011. Section 11.

- Bennett G. Infection Prevention Manual for Long Term Care; 2012. Rome, GA: ICP Associates, Inc.; 2012. Section 11.

- Lautenbach E, WoeltjeKF, and Malani PN, eds. SHEA Practical Healthcare Epidemiology (3rd Edition). University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL 2010. Chapter 5 Quality Improvement in Healthcare Epidemiology, by Susan MacArthur, Frederick A Browne, and Louise-Marie Dembry

- Mayhall CG ed. Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control (4th Edition). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business; 2011.

- Chapter 11, Selecting Improvement Projects, by D Birnbaum

- Chapter 12, Conducting Successful Improvement Projects, by M Segarra-Newnham and RG Berglund

Helpful Contacts (in WY or US)

- Mountain-Pacific Quality Health-Wyoming, 307-472-0507

Related Websites/Organizations

- Wyoming Department of Health, Infectious Disease Epidemiology Unit, Healthcare-Associated Infection Prevention https://health.wyo.gov/publichealth/infectious-disease-epidemiology-unit/healthcare-associated-infections/

- State of WY Healthcare Facility Specific regulations, health.wyo.gov/ohls/index.html

- Mountain-Pacific Quality Health – Wyoming mpqhf.com/wyoming/index.php

- Association for Professional in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). apic.org

- Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) shea-online.org

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Quality and Safety, ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/index.html

- Wyoming Infection Prevention Database of Resources, wyohospitals.com/wipag.aspx

- The Joint Commission, jointcommission.org

My Facility/City/County Contacts in this Area

Develop a list of contacts (include their phone number, email, facility/company, address, and area of expertise). Resources may include sources such as APIC members, other IPs, QIO contacts, State employees.

References

- Wyoming Department of Health. Appendix A – Survey Protocol, Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines for Hospitals. State Operations Manual. wyohospitals.com/_pdf/2013/january/Survey%20Protocol,%20Regulations,%20and%20Interpretive%20Guidelines%20for%20Hospitals.pdf. Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Bennett G, Morrell G and Green L, ed. Infection Prevention Manual for Hospitals; revised edition. Rome, GA: ICP Associates, Inc.; 2010.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Quality Improvement 2011. www.hrsa.gov/quality/toolbox/methodology/qualityimprovement/index.html. Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality. CUSP: The comprehensive unite-based safety program – Appendix N. armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/csts/cusp/resources.aspx. Accessed November 7, 2013. Used with permission of the Johns Hopkins Medicine Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality.

- US Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration. Developing and Implementing a QI Plan 2011. hrsa.gov/quality/toolbox/508pdfs/developingqiplan.pdf . Accessed November 7, 2013.

- American Hospital Association. Trendwatch Oct. 2012. aha.org/research/reports/tw/12oct-tw-quality.pdf . Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Lee F, Lind N. The Infection Control Committee. Infection Control Today. June 2000. infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/2000/06/the-infection-control-committee.aspx . Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Hoffman K. Developing an Infection Control Plan. Infection Control Today. Dec. 2000. infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/2000/12/developing-an-infection-control-program.aspx. Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies. ahrq.gov/clinic/epc/qgapfact.htm . Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Patient Safety. Root Cause Analysis. patientsafety.va.gov/professionals/onthejob/rca.asp. Accessed Nov. 7, 2013.

- Wald H, Shojania KG. Root cause analysis. In: Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, et al, eds. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058: 2001. ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/ptsafetyuptp.html. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Failure Modes and Effects Analysis Tool. ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/FailureModesandEffectsAnalysisTool.aspx. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Mind Tools. Business SWOT Analysis. mindtools.com/pages/article/newTMC_05.htm . Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Tague MR, ed. In: The Quality Toolbox. 2nd ed. Milwaukee, WI: American Society of Quality, Quality Press; 2004: 359.

- Khorafan F. Quality toolbox daily goals checklist: a goal-driven method to eliminate nosocomial infection in the intensive care unit. Journal of Healthcare Quality. 2008; 30(6):13-17.

- Wiemken T. Statistical Process Control. In: Carrico, R, ed. APIC Text of Infection Control Epidemiology (3rd Edition). Washington, DC: Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc., 2009; Chapter 6.

- Six What is Six Sigma? www.isixsigma.com/sixsigma/six_sigma.asp . Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Testing for Change. ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementTestingChanges.aspx . Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Langley G, Nolan K, Nolan T, Norman C, Provost L. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; Second Edition, 2009.

- Hafner, J M, et al. The Perceived Impact of Public Reporting Hospital Performance Data, Interviews with Hospital Staff. International Journal of Quality Health Care. 2011; 23(6):697-704.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). cdc.gov/nhsn/acute-care-hospital/index.html . Accessed November 7, 2013.

- The Quality Indicator Study Group. An approach to the evaluation of quality indicators of the outcome of care in hospitalized patients, with a focus on nosocomial infection indicators. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 1995; 16:308-316.

- Yokoe DS, Classen, D. Improving Patient Safety Through Infection Control: A New Healthcare Imperative. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2008; 29: Suppl 1.

Appendices

Please download the printable PDF Version of this section, linked at the top of the page, to view the following appendices:

Appendix A: John’s Hopkins Barrier Identification and Mitigation Tool

Appendix B: Infection Control Risk Assessment Tools

Appendix C: Infection Control Risk Assessment Documentation Templates

Appendix D: Infection Prevention Plan Guideline and Associated Templates

Appendix E: The Nursing Process

Appendix F: Plan Do Study Act Template and Example

Appendix G: Plan Do Study Act Template

Appendix H: PDSA CLABSI Example

Appendix I: Healthcare Facility HAI reporting Requirements to CMS via NHSN

Appendix J: Surgical Center Reporting Measures

WIPAG welcomes your comments and feedback on these sections.

For comments or inquiries, please contact:

Cody Loveland, MPH, Healthcare-Associated Infection (HAI) Prevention Coordinator

Infectious Disease Epidemiology Unit,

Public Health Sciences Section, Public Health Division

Wyoming Department of Health

6101 Yellowstone Road, Suite #510

Cheyenne, WY 82002

Tel: 307-777-8634 Fax: 307-777-5573

Email: cody.loveland@wyo.gov

The material for this section of the WY IPOM was prepared by Mountain-Pacific Quality Health, the Medicare Quality Improvement Organization for WY, MT, HI and AK, under contract with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Contents presented do not necessarily reflect CMS policy. 10SOW-MPQHF-WY-IPC-12-08